Symbolic Execution

klee llvm sat symbolic executionA while back, I had the opportunity to collaborate with my colleague, Philippe Gabriel, on a research project focused on automating defect finding and enhancing overall test coverage. Our primary concern at the time was null pointer dereferences, which had the potential to cause system-wide crashes. In our quest, we explored various strategies and tools, both free and commercial. However, what truly captured our interest was a fascinating area of research called “Symbolic execution.” Imagine having a tool that could automatically identify critical bugs in your source code with minimal or no false positives, while also generating input stimuli to trigger those bugs.

I want to acknowledge the significant contributions made by Dawson Engler at Stanford and Patrice Godefroid at Microsoft Research in advancing this field of research. Their detailed papers are captivating and offer valuable insights.

In this article, I provide background information about symbolic execution. In a future post, I will delve into its practical applications, utilizing frameworks such as LLVM and klee).

Introduction

In recent years, static code analysis has made remarkable progress, allowing its application to large real-world codebases and generating reliable results. A crucial metric for success in this area is the ratio of actual defects to false positives. Achieving an optimal ratio is an incredibly challenging problem that involves employing heuristics, optimization techniques, and fine-tuning. One of the most significant advantages of static code analysis is that it analyzes the source code itself, eliminating the need to build, link, and run the code under scrutiny. It operates on “snippets” of code, which are perfectly valid in isolation.

Unlike other code analysis tools, symbolic execution executes the code under test in a controlled environment or virtual machine. The key distinction from normal execution is that certain inputs are treated as symbolic, meaning they can be “anything.” For code that depends on symbolic input, the symbolic executor constructs boolean expressions (known as path constraints) to explore previously uncharted paths.

Symbolic Execution

Symbolic execution involves “executing” a program in an abstracted manner. Let’s examine the process using the following code fragment:

int* func(int x, int y) {

int* p = 0;

int s = x * y;

if (s != 0)

p = malloc(s);

else if (y == 0)

p = malloc(x);

return p;

}

Suppose our goal is to ensure that func always returns a valid (non-null) pointer.

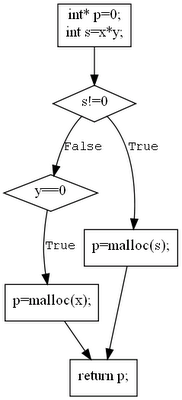

Control Flow Graph

The first step in symbolic execution is to generate a Control Flow Graph (CFG), which provides an abstract representation of the code in the form of a directed graph. In the CFG, each node represents a “basic block” terminated by a conditional statement (in this case, an if statement). Each edge corresponds to a boolean “truth value” for the condition.

Generating the CFG helps visualize the paths of execution. It’s worth noting that CFGs are not specific to symbolic execution; compilers also generate CFGs during code compilation as they lend themselves well to optimization techniques.

Analysing the CFG with symbolic values

With symbolic execution, our objective is to identify feasible paths that lead to undesirable outcomes or “bad things.” In this scenario, we aim to find the path(s) that result in returning p without it being allocated first. To understand how the value of p changes, we assign a symbolic value to p at each node in the CFG. In other words, we’re interested in the symbolic value of p; we don’t care about the specific memory location it points to. Our focus is solely on whether p is null or non-null.

By annotating the CFG accordingly, we can easily identify a path that leads to returning p without prior initialization. This simple example demonstrates two fundamental techniques in practice:

- Transformation to CFG

- Reasoning on symbolic values

Note that we also draw implicit code paths, as they lead to different symbolic value of p.

Scalability and Accuracy

Developing a “symbolic tool” poses numerous challenging problems. Broadly speaking, these problems can be classified into two categories:

- Scalability and speed of analysis: Analyzing a non-trivial function involves a large number of paths. Ideally, we want the tool to complete its analysis within a reasonable timeframe, avoiding prolonged execution.

- Accuracy: Not all paths are feasible, and reporting defects along infeasible paths leads to false positives. A practical tool should only report genuine errors and provide test vectors to reproduce those errors.

Consider a simpler tool like a “lint” tool, which becomes less useful as it generates excessive “garbage” output. An ideal tool, on the other hand, would report only real errors and provide test vectors to trigger those errors, as you’ll see later in this article.

Scalability and Inter-Procedural analysis

The scalability problem is compounded by the fact that we can’t limit the analysis to paths within a single function for any non-trivial analysis. For example, in the previous code snippet, it doesn’t matter if func returns a null pointer if all callers of func properly check for this possibility. To conduct a meaningful analysis, we must follow the path until the pointer is actually used. This necessitates analyzing paths that span multiple functions, which is known as inter-procedural analysis.

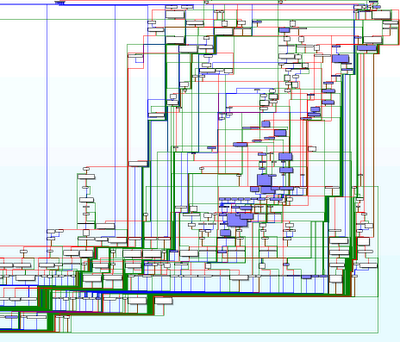

Performing inter-procedural analysis enhances accuracy, but it exponentially increases the number of paths to analyze. A real-life CFG, taking inter-procedural analysis into account, is likely to be more complex:

An exhaustive enumeration of paths through such a CFG would never complete. Consequently, researchers and practitioners in this field focus on techniques to prune the CFG and identify a small set of “interesting” paths. The path explosion problem can be mitigated using heuristics derived from graph theory or by inferring additional information from the execution context.

Accuracy

Analyzing long paths introduces a complication: the path conditions along those paths may be unsatisfiable. Let’s explore this concept in more detail, as it leads us to another fundamental idea underlying symbolic execution.

Path Condition

Let’s revisit the previous example and discuss path conditions. We’ll rewrite the CFG, incorporating the truth values of the encountered conditions along the given paths. The path condition represents the boolean equation that synthesizes the truth values of the encountered conditional expressions at each node.

For the path of interest (leading to a null p), the corresponding expression is x * y == 0 && y != 0. Thus, we can associate a set of boolean equations with each edge along a given path. In this example, we can conclude that x * y == 0 && y != 0 implies p == 0.

Inter-Procedural analysis and Path condition

Now that we understand path conditions, let’s explore how they help solve the accuracy problem. We need to determine whether a path that appears feasible within the narrow context of a single function is valid in the larger context of the entire program, which involves interprocedural analysis. For instance, we might discover that all paths containing a call to func have an ASSERT statement before the call, checking if x is not equal to 0.

//func as defined above

int* func(int x, int y);

//main calls func

int main() {

int x,y;

int p*;

...

ASSERT(x!=0);

p=func(x,y);

...

}

The path condition now becomes x * y != 0 && y != 0 && x != 0. It is evident that this boolean equation cannot be satisfied, which aligns with the concept known as the Boolean Satisfiability Problem.

Boolean SAT applied to Symbolic Execution

Now, let’s delve into the good news and the bad news…

The bad news is that solving the Boolean Satisfiability Problem is an NP-complete problem, meaning it is inherently complex and does not have an upper limit on its running time. Although not explicitly apparent in this simple example, any non-trivial path can be summarized by a path condition with hundreds of terms. Therefore, simply iterating through all possible assignments for boolean variables would lead to infinite execution.

The good news is that there are solutions to this problem. The Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) industry, for instance, has been dealing with solving boolean equations with a large number of terms for years. They have developed fairly efficient software, known as SAT solvers, to tackle this challenge. In fact, researchers continually refine algorithms for SAT solvers to solve ever larger boolean equations in a more efficient manner.

Consequently, modern symbolic execution engines incorporate these SAT solvers. A boolean SAT solver can quickly determine that x * y != 0 && y != 0 && x != 0 is unsatisfiable, thus avoiding the reporting of a false positive defect.